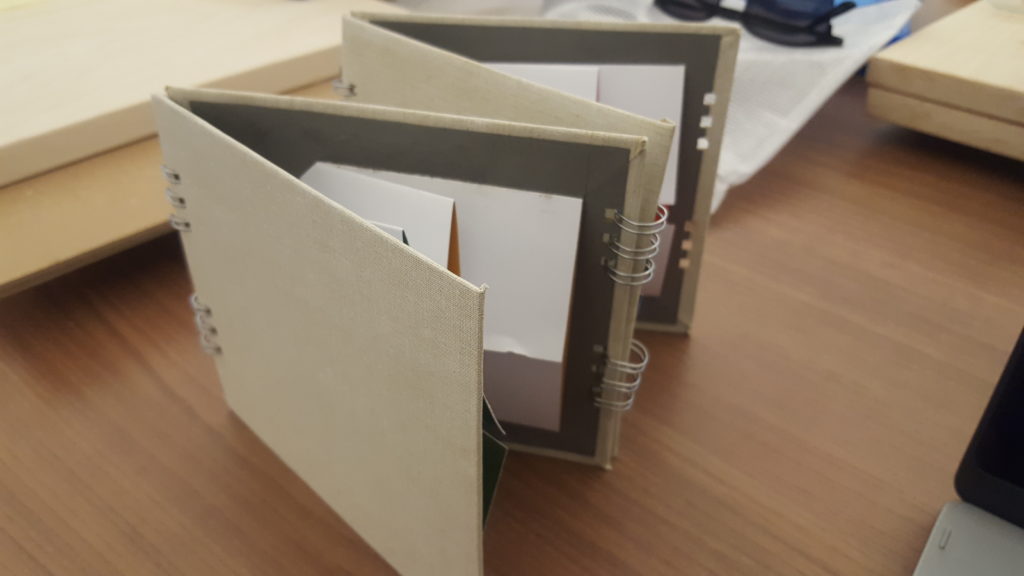

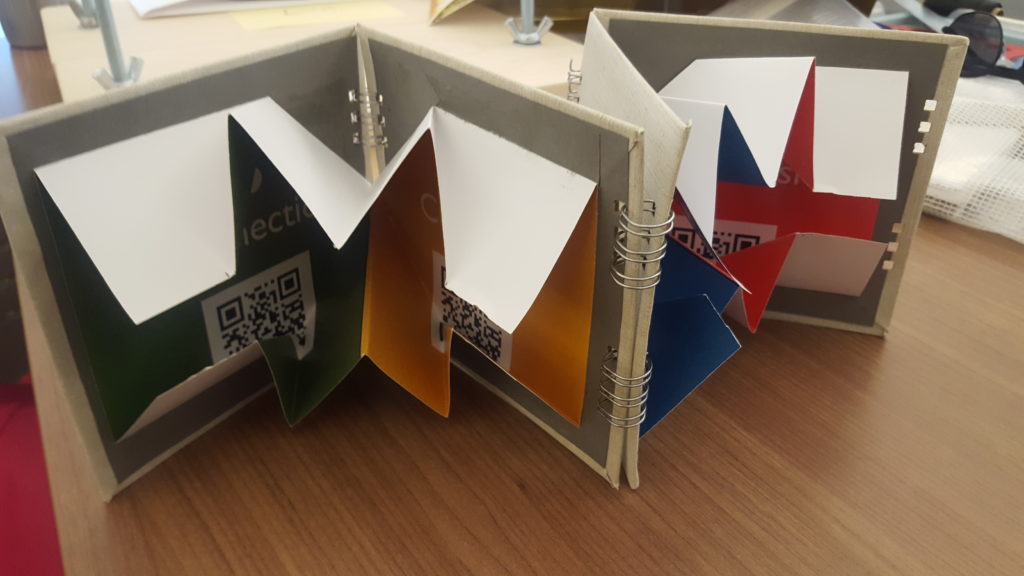

My final project for this NEH Institute, “Literacy in Flex.” It’s a coil-bound book with a Turkish-map fold. QR codes are embedded on the insides of the pages.

I have to admit that I almost shed tears at the thought of sewing pages together today.

It’s the last full day for us here to complete the projects that we’ll be exhibiting at the Salt Lake City Public Library and I had only a few steps left for the project I had conceived: bind the covers of my “book” together and glue the pages inside the covers. Foolishly, I assumed that these remaining tasks would be simple and would leave me with plenty of time for contemplation and a little bit more writing on a book proposal that I’ve been drafting. But it soon became clear that I could not just tape my covers together to create a binding, nor would gluing the pages on to the covers be quite as simple as running a glue stick across the back of the page, slapping it on to the cover, and calling it done.

As it turned out, the tape I imagined I would use for creating the flexible binding on my project would not stick to the book cloth material with which I had chosen to drape my covers. I turned to a couple of the organizers for this institute, and when one of them suggested stitching the covers together, I felt myself go pale at the thought.

I gave the “simple” stitching a try on a piece of scrap book board, but when I poked myself with a needle and saw the tangle of thread emerge out of the holes in the book board, I just felt my heart sink into despair. A part of me did not want to resist the stitching, especially if it was going to be the most secure way to hold the book together, but I couldn’t fight the feeling of frustration, of how long it would take for me to do something seemingly so simple.

For those of you following me along through this journey, my reflections on my frustration probably feel a bit familiar. My experiences of learning to make different kinds of books – different ways to convey and provide the structure for information – often led to moments where I felt emotionally more distraught than I perhaps should have felt. Beyond the immediate reaction that I sometimes couldn’t always do something as quickly, efficiently, or neatly as others could around me, my reactions also stemmed from my own awareness that my functional literacy, my ability to work with tools, was woefully limited. As someone whose job title – “Academic Technology Specialist” – denotes significant fluency in using technology adeptly, I felt like the world’s biggest fraud, unable to do the simplest, indeed the most analog, of technological tasks. For a long time, I’ve touted the needs for students to develop multiple literacies, including the ability to make things with some skill, and yet I felt barely capable of doing so myself. Indeed, I often encourage people to adopt the tools that best respond to their particular communicative needs, and yet, when faced with a moment when it seemed like stitching would best respond to my particular needs, I felt utterly defeated, recognizing that the “best” tool would challenge me in ways that invited significant material and emotional labor.

Once again, I felt reminded of feelings I’ve had around learning how to code. When I’ve worked on websites, I’ve known that certain coding languages would do a better job than others for accomplishing certain kinds of communicative goals. Sometimes, I would just suck it up and learn the code. At other times, I found myself seeking out alternatives, ways to work around my limitations to make the project happen.

In the case of my book project, both of the organizers helping me sensed my frustration (both, at different points, gave me hugs because I’m very bad at hiding my feelings!). So, they did what I often do when I’m working with faculty who are struggling with using a particular digital tool: brainstorm other possibilities. When one suggested using a coil binding to put the book together, I felt immediately relieved. Yes, coils! We could use a machine to punch little holes into my covers and then allow that same machine to tighten some coils around the edges, and voila, a book with hinges would exist!

While I don’t necessarily believe in avoiding a challenging task just for the sake of avoiding the labor, my experience today reminded me of how important it is to think critically about how you plan to engineer a project of any kind and consider that there are always multiple ways to complete the project. The coil binding was not exactly easy (it still took a fair amount of precision work, and I wound up making an unintended and irreversible mistake of punching a few extra holes. Oh, well!!). But it solved the problem without causing me to lose a few years from my life, as the stitching inevitably would have done.

What the book looks like when it’s opened up.

There is a lot to unpack from this experience, but I think the most important lessons I learned today were to be 1.) unafraid to think creatively through a problem, 2.) allow myself to be OK with feeling upset about something and find a way to use that reaction to make a decision, and 3.) patient (yet again) with myself and understanding of the need to re-calibrate expectations. I’m certainly guilty of getting attached to initial visions of ideas (whether those are written arguments or multimodal projects, like the one I made for this institute). Almost every project I have ever done has involved abandoning part of what I created in lieu of another solution, and building something multimodal is no exception.

At almost every stage of this project, I’ve wound up shifting or compromising certain ideas in order just to get something completed, and I suspect that this will not be the last time I’ll experience this feeling. As I look ahead to writing a book this year (aaaah, eeeek), I’m recognizing already the importance of maintaining an open mind about what form the ideas might take or how I might be challenged to adapt the form and content of that book at any stage of the project.

Flexibility is, in other words, one of the greatest practices I can continue to adopt as I look beyond this very special and protected institute space.

To that end, and very much in homage to my experiences, my project is titled “Literacy in Flex.” For those curious about my reasoning on why I designed my project this way, here’s the annotation that will be on display at the library:

“Literacy In Flex” is a coil-bound, map-fold book that invites readers to think more critically about what reading and writing can look like in a digital age. We sometimes think of “reading” and “writing” as linear acts that only happen in a few narrow contexts. Symbols for representing literacy (e.g. the pencil, the typewriter, the bound book) tend to focus on literacy as a print-based practice when, in fact, many acts of literacy now happen in a variety of composing spaces, from digital spaces like laptops and smartphones to mobile paper spaces like Post-It notes and paper napkins. When we limit our vision of what “literacy” is to print-based practices, we, at best, narrow our imagination of what’s possible when we read and write, and at worst, exclude or ignore visions of who can participate in literate acts. This book, therefore, lists four key literacy strategies for a digital age on each of the four colored panels. Scanning the QR codes on each panel will take users to a webspace I’ve created that defines each of these four strategies and examples of how those strategies could be enacted (via blog posts I wrote during my time at this NEH institute). The map fold book is intended to show that, when we “open up” our vision of what literacy can be, we experience an expanded sense of what literacy looks like. Therefore, when our conception of reading and writing is “in flex,” we can invite a greater diversity of people to acts of reading and writing.