The outside wall of Ken Sanders Rare Books shop in Salt Lake City, UT.

“This was a well-curated day!” exclaimed one of my NEH institute colleagues as we waited for our train in downtown Salt Lake City.

Indeed, we enjoyed a rather full and playful break day from the institute, starting with a tour of Temple Square and the Tabernacle (visitors are not allowed inside the Temple itself, which is a giant landmark in SLC), moving on to a vegan lunch complete with beet-ginger-apple mimosas, a visit at the Utah Arts Festival, and ending with a trip to Ken Sanders Rare Books store. I could write an entire post about all of these travel experiences, but for fear of veering a bit too off-brand here (a travel blog will have to wait for another day and space, I’m afraid), I actually want to write this post a bit about curation.

From the first day of the institute, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around the role of curation in reading and writing. “Content curation” is a concept I’ve been talking to my students a lot about at Stanford because, fundamentally, being a good researcher and writer is a lot about knowing which information to use and how to put that information together into an argument. (Plus, the concept of curation is a rather sticky one in the world of tech industries, a world that many Stanford students want to enter). We have to curate the information that we gather in order to, well, make sense of the vast amounts of information in the world! The more that we curate content into a linear narrative, the more easily we can communicate with others. In a digital environment where there is more accessible information at our fingertips than ever before, the ability to curate content becomes all the more important. To make this even more concrete, social networks are a classic space where people curate content: on Pinterest, for example, people curate boards of “pins” which collate everything from recipes and workout routines to interior decor and “life hacks.” Content curation at its finest.

Yet how we might think of curation as an ethical act? At what point do we curate to such an extent that we exclude particular voices? At what point is keeping everything we can possibly find an act of excess that problematically quiets all of the perspectives involved? To what extent does curation become a choice about what gets archived forever and what gets lost to the annals of time?

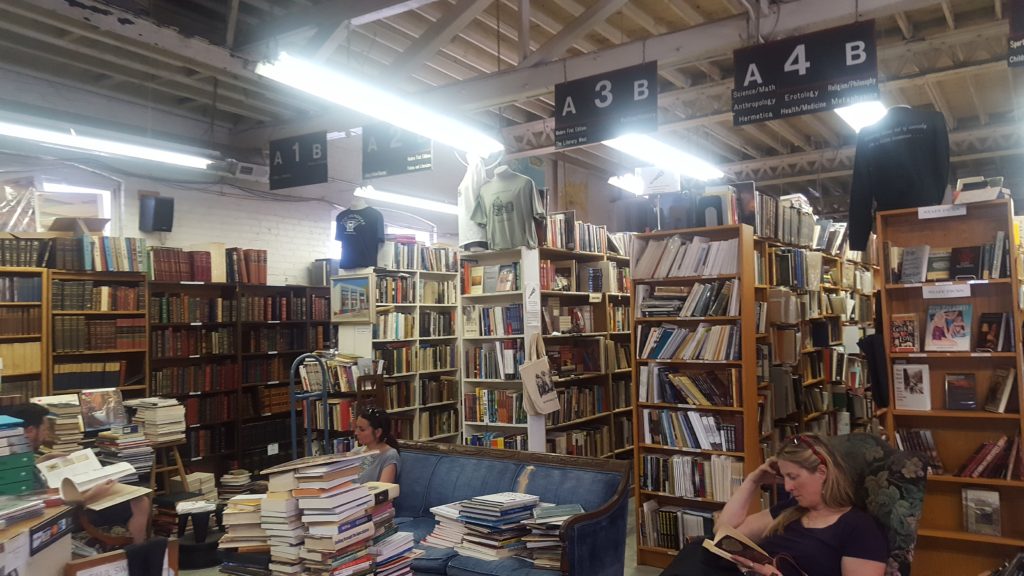

Especially as I visited Ken Sanders Rare Books store today, I felt a sense of complete overwhelm at the stacks upon stacks of books, many of which were not only catalogued on the shelves, but were piled on top of tables, chairs, and even stairwells. In spite of the labels hanging above each of the aisles, it was not exactly easy to find anything in particular; this was a bookstore where you, as a consumer, had to curate and sift through the content yourself. There were no staff recommendations. There were no book club lists. There were only books sorted broadly by literary genre (a distinction that matters very little in deciding what to read for me, anyway).

The inside of Ken Sanders Rare Books store, an independent new, used, and rare books store in Salt Lake City, UT.

In many ways, it reminded me of the experience of browsing a web catalogue. While I might browse a bit more purposefully online than I would when perusing a bookstore, I still found myself flitting from book to book at the store in the same way that I might flit from tab to tab in my browser. There was a special joy of the shop in imagining the serendipitous possibilities of encountering something precious, rare, and resonant, but I also understood that the patience required to look through all of these books to find a potential hidden gem actually required a kind of literacy: the ability to know what makes a book valuable. For me, I was struck by how little I knew about the books themselves. Sure, I could recognize lots of authors and titles, but I had no clue how I would decide whether to buy something or even whether I could discern if a book had significant monetary value. The stakes of these choices obviously look very different in an online space (insofar as online articles do not have the same kind of material, archival value as old print books – yet!). Yet I couldn’t help but consider how close this experience was of feeling overwhelmed at the used book store to the feelings I often experience when I’m trying to decide what online article I want to settle into or what link on Twitter I actually want to read instead of simply “favorite” and save for later.

So, to return to my thinking about curation, I wonder whether curation is not the most important skill we could teach students in a reading and writing class. I think that lessons about curation already happen to some extent; any lesson about note-taking or highlighting is a lesson about curation. But I think our classes, especially in a higher ed context, could play with this idea even a little bit more. I’m actually thinking that it might be interesting to do an activity where I ask students to explain what their process is for picking a book at a bookstore or buying a book off of Amazon. I bet I would find that many students are making curatorial choices about what to read based on friends’ recommendations or name-brand value and recognition. This conversation could easily veer into a discussion of taste, but if I were skillful enough, I think it could also turn into a fascinating conversation about the cultural situatedness of how we decide what to read. I also think the conversation could get us to a point of thinking about preparing ourselves to be literate in the 21st century: the more that we understand our heuristics for making choices and curating content, the more that we’re away of how critical a role curation plays in shaping our beliefs, our values, and our ability to learn new content, perhaps we can become more sophisticated curators moving forward.

Humans, on the whole, are pretty bad at curation. Just look at sidewalk garage sales or flea markets: our lives are full of things that we probably don’t need, that we don’t know how to weed out, and that we don’t know how to decide if it matters or not. Yet if we developed some metacognitive awareness about curation, maybe we could be just a little bit better at it. That’s my optimistic take for the day, a day where very little work happened, but where I got to absorb a lot of beautiful things in Salt Lake City, and curate my own experiences into a collection of photos and words.