In roughly 3200 B.C., people used mobile devices. Sumerian clay tablets weren’t exactly like smartphones, but they had a lot of the same benefits: you could hold them in the palm of your hand, you could access records of past transactions or conversations, and you could take them with you wherever you went. They perhaps even had the added bonus of being environmentally friendly. Because they were made of clay, they could be easily recycled and reused; simply by dunking the tablet into a vase of water, a user could allow the clay to soften and get re-formed for the next communicative exchange.

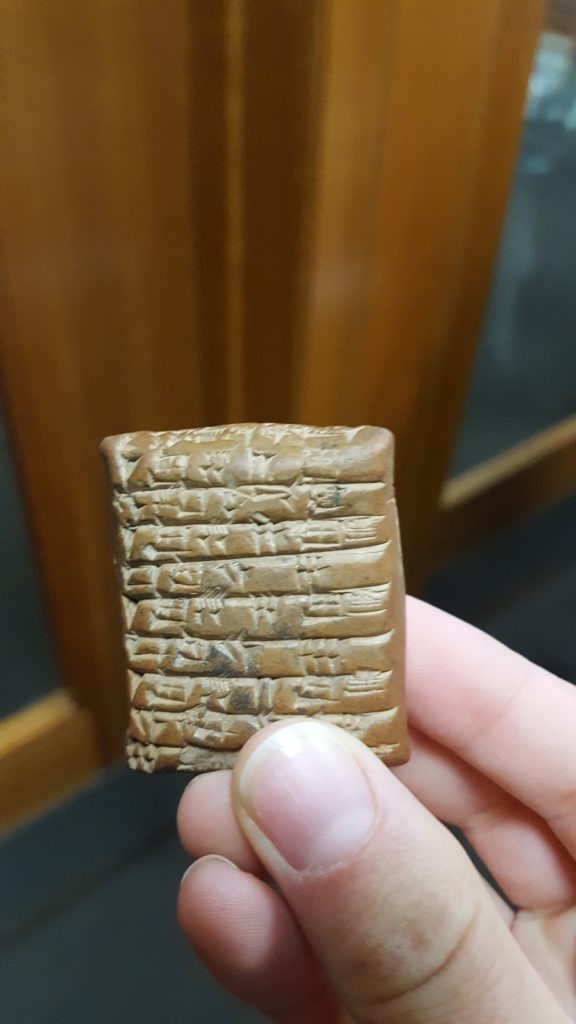

A Sumerian clay tablet in the archives of the Brigham Young University (BYU) library.

Holding one of these tablets while visiting the archives at the Brigham Young University (BYU) library yesterday, I felt struck by how usable the tablet was. While I had no idea what words or ideas were written on the tablet I held – the librarian informed us that the tablet was probably just a receipt for a financial transaction (one goat and five chickens please!) – I could imagine how simple this could be for an ancient person to have used. Every item is clearly delineated on a line. The scribe takes full advantage of the space, crafting words from the top of the tablet’s ridges to the very bottom. Then, the tablet is passed off, hand-to-hand, mobile and efficient.

I thought of this tablet immediately from a user experience research perspective. I don’t know enough about the context for how the tablet was used to fully understand how it might apply to something like Nielsen’s user experience heuristics or a framework that would help me understand whether this information design worked, but seeing this tablet got me thinking a lot about what parts of our information infrastructures, like books and computers, are usable because of (normative, able-bodied) human mechanics or are usable because of cultural constructions. Specifically, the fact that we’ve turned back to using mobile devices for so many of our communicative interactions hearkens back specifically to one of the main affordances of this Sumerian clay tablet. Things have changed on smartphones insofar as the content is dynamic, networked, and globally accessible. Yet the idea that our bodies – the fact that humans are interested in holding things close and having things in the palms of their hands – has not changed our interest in using something like a “mobile” technology. I’m not quite sure what to do with this thought yet, but it stood out to me from our experience of exploring the archive and its early books.

This conversation got extended during our seminar discussion today where a visiting scholar, Dr. Nicole Howard, came and visited us to discuss her book that we read, The Book: The Life Story of a Technology. Our conversation went through and around a lot of these questions about usability: historically, what makes something like the modern, paperback book such a sustainable, practical, and usable technology? Why do we still draw upon the logic of silent, print-based information when, in a digital age, we could be drawing even more heavily on orality, for example (especially in school contexts)? That’s not to say that we aren’t, but popular conceptions of “literacy” still seem, to me at least, be very narrowly tied to the experience of reading from a paperback book bound in pages. Perhaps it’s the haptic, the connection to our hands and our bodies, alongside the tactility and responsiveness of paper. But I don’t know. There’s a lot more there and my brain is honestly a bit fried from all of our copious conversations today to fully process this thought.

There’s a lot more to unpack here, but I’m afraid other thoughts to this end will need to wait until tomorrow. I’m pinning this idea on usability because I think it’s generative and helps us to also understand how a book is accessible (or not). If you’ve got thoughts on the intersections between book history and usability, let me know!