Mid-way through week 2 of this institute, I finally feel comfortable in my routines, moving through each day in a kind of steady rhythm of breakfast, discussion/lecture time, workshop time, exercise, dinner, writing, reading, sleep. It’s a simple routine, one that feels a little bit like being in college again. By residing at a long-term stay hotel, many of my meals are prepared for me, and I return every day to my room with my floors vacuumed, my bed neatly made, my towels tidily arranged. It’s luxurious, really, and I don’t know if I’ll ever have protected time like this to drill deeply into an intellectual topic with a community of peers again. The odds are unlikely.

Given how special this time is, I’ve attempted to shield myself a bit from the news, deliberately trying to focus my energy on the questions, conversations, and provocations offered here. I have high hopes that the long-term project I’m working on (i.e. a book of my own) will have some impact on its readers, insofar as it could change a few minds (isn’t this what we all aim to do with our writing?).

Yet I found it hard to focus today. The current events of family separations at the border and the breaking news today of Justice Kennedy’s retirement started to weigh on me. My project on responding to notions of “literacy crisis” in a digital age started to feel pretty irrelevant in light of the human atrocities occurring now and the potential rollbacks on women’s rights, minority rights, and social progressiveness looming in the future. I wondered whether the whole exercise of sequestering myself in a community of scholarship was something silly and self-indulgent.

I don’t think I was the only one feeling this way today. Something worth knowing about communities of scholars is that we all tend to harbor a lot of similar values around social justice. Indeed, many of us (if not all of us) will be attending a rally at the Utah State Capitol to stand against the cruel separations of children from their parents at the border. Indeed, the interest in social justice seemed to pulse through the undercurrent of both of our seminar time and our workshop time today as we discussed, of all things, the legacy (and future) of the broadside.

Before this week, I had no idea what a broadside was. Turns out that a broadside is, quite simply, just one large sheet of paper where the printing only appears on one side. How is this different than a poster, you ask? Well, it’s not, really, but the broadside has a more complex historical legacy than a poster. See, broadsides became a popular way in the Western world (read: England primarily, but I’m sure there’s a history outside of the Anglo world to broadsides that I just don’t know anything about so pardon my ignorance here if I’m missing a nation in this conversation) to share public news, current events, songs, stories, or advertisements, starting as early as the 16th century. Broadsides were never really meant to be saved for long; they are considered ephemeral documents, used only to catch the eyes of passersby on city street posts (not unlike the posters you often see around college campuses today!). Plus, broadsides were often meant to be read aloud, particularly for people who saw the broadsides on the streets, but who could not read them for themselves (literacy rates from the 16th-18th centuries in England were a bit spotty, so listening was a particularly powerful form of learning content).

So, can you imagine the scene? A crowd gathers at a street corner. A man, adorned in a top hat and coattails, unfurls a broadside before him and projects in a booming, sonorous voice, a particularly salacious piece of news or a legal declaration that impacts the citizens of that very street corner. The response would be immediate, visceral, fully embodied. In other words, I can imagine that hearing a broadside probably felt a lot like hearing a broadcast on the radio or seeing a breaking news story on television. And if you happened to encounter a broadside outside of the public performance, it probably felt a little bit like scrolling through your news feed and stumbling upon a story that captures your attention. Ephemeral media, in other words, is vital to our literate lives, and has been for a long, long time.

The broadside was used in a lot of different contexts, of course, and not always for the good. But broadsides could often function in a kind of subversive way, offering news from the people of the people to the people. A question I asked during our discussion about the broadside was, “Who is the audience for the broadside?” At first, I couldn’t really understand what social work the broadside accomplished because my understanding of documents, of genres, often comes out of knowing first who the text is written for. As my peers around the room responded to this question, the answer became clear: the broadside’s form changes, ever so slightly, depending on who the broadside might benefit. In other words, broadsides were written for multiple and different audiences, and the social action that the genre performs is really, beautifully simple: to announce something with a mix of visual (via the large headers of print, the inclusion of images) and verbal engagement (via the public performance of being read aloud).

This announcement may not always be as dry as a news headline from the New York Times. Rather, the announcement tended to be quite lyrical, and the announcements often took the forms of ballads, a poetic form that resembles a kind of song or sea shanty. (See “Keep Your Powder Dry,” a war cry out of England circa the 19th century).

Examples of broadsides courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries online Broadsides Collection. (http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/)

We don’t really make broadsides like these anymore, but we do make posters, and a lot of them, especially given the proliferation of protests since November 2016. So, when we were tasked to try our hand at broadsides today, I did it. And I made a poster for Saturday’s march.

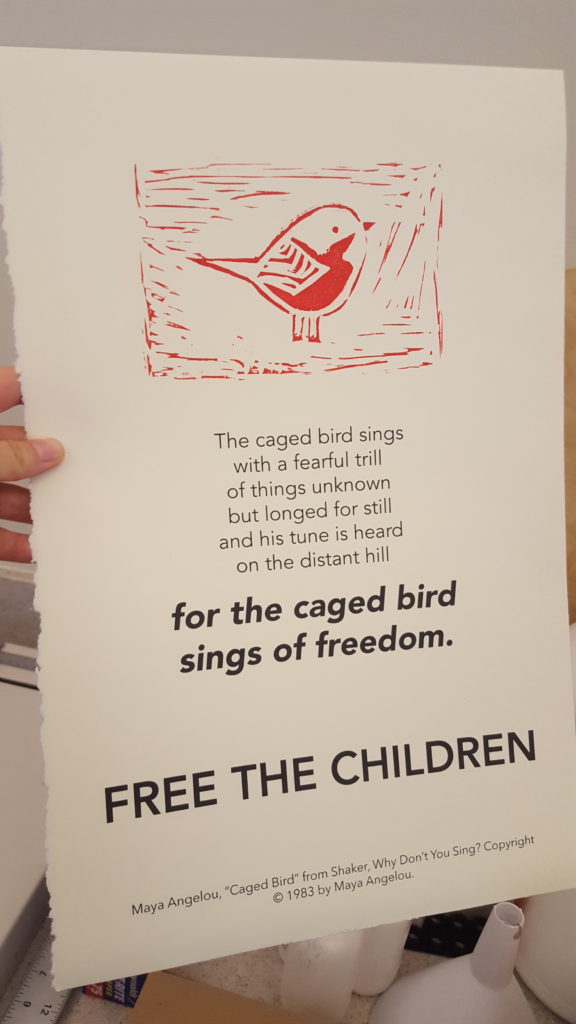

The poster I’ve made for the Keeping Families Together rally on June 30th at the Utah State Capitol. The lines are from Maya Angelou’s “Caged Bird” poem.

The process of making my version of a “broadside” felt cathartic today. While I lean much more heavily on long-form text and publication as my main form of communicating with others (and digital dissemination via this blog and other online journals I write in), I understand that the embodied space is powerful. All effective communication, I’m increasingly convinced, involves the whole human sensorium, and any moment when we can bring people into our ideas with sight and sound and touch is a good moment indeed.

I was drawn to the image of the bird for this broadside first, and the stamp itself comes from a lino cut made by one of our program’s facilitators, Charlotte. I feel a certain affinity to birds, and as soon as I saw this stamp (again, technically a lino cut, which just means that the stamp itself is made from a piece of carved linoleum), I thought of Angelou’s poem, “Caged Bird.” I then thought of the images I’d seen in the news of children in their own kinds of cages. And then I knew that this was the poster I wanted to make.

The work of getting out, being in the world, being heard, and being read is challenging work. It puts our bodies and our ideas on the line. But that is the work that needs to continue happening. Making that work of communicating in multiple modes and spaces visible – and understanding that work as literacy development – is what I hope to continue sharing and helping others understand moving forward.

Brava!

Thank you!!